by Hazzan Barbara Barnett

This week’s Torah potion is called Vayikra, and it begins the third book of the Torah The first word of Vayikra contains a scriptural anomaly. (Can you spot it?)

Something here a bit strange and unexpected and might make you think the scribe who created the Torah scroll erred with his quill pen. —an aleph. It is superscripted and quite tiny. The question is “why?” Speculating about the “why” has puzzled Biblical scholars for centuries.

The word “Vayikra” means “He called,” referring to G-d calling out to Moses. Often in the Torah, G-d “speaks” to Moses, He “says” to Moses. But here he “calls out.” But the aleph in Vayikra seems ambiguous. Is it meant to be there or is it an error of some sort? It may to some seem a trivial matter, but the presence or absence of that one letter vastly changes the meaning of the text.

Without the aleph, the word becomes vayikar—by chance—a chance encounter and not the definite “call” out to Moses from G-d. It’s tiny thing, but significant. Numerous scholars over the generations have commented and interpreted the meaning of this seeming scribal anomaly.

Rabbi Dr. Jonathan Sacks suggested that the “aleph” is written so small to emphasize that G-d calling out to us is not always done in the grand gestures and miracles like the splitting of Reed Sea or the sending the signs and wonders in the lead up to the Exodus, which we commemorate on Passover. Sometimes G-d’s presence nearby, calling out to us, abides in the quiet gestures of the day-to-day of our lives. That the small coincidences, the happenstances, so easy to dismiss, may indeed by G-d calling—not vayikar, but vayikra. Easy to miss, unless you attune yourself to the everyday miracles, signs and wonders, which help us draw near to G-d. As the korbanot, the offerings described in such detail in Vayikra are meant to accomplish, and the Hebrew word “korban” implies.

This sense of G-d’s presence signified by the difference between “vayikar” and “vayikra” calls to mind my favorite quotation from Albert Einstein, “Coincidence is G-d’s way of remaining anonymous.”

From our home to yours, Phil and I wish you a wonderful Pesach.

Print This Seder Supplement – Your Seder Conversation-Starter

Rabbi Alex Freedman

|

|

| Seder Participant Supplement – click on link to open and print | Seder Leader Supplement – click on link to open and print |

Here are four new Passover questions I have for you:

1. Has your Seder discussion gotten stuck?

2. How do you take this ancient story and refresh it for 2021?

3. How do you engage both kids and adults?

4. How do you interest both Seder rookies and veterans?

Leading the Seder conversation is a challenge. Let the Seder Supplement help you. (No, it’s not too early to think about as we are only about two weeks away!)

I prepared this updated handout to spark a table discussion. (A big thank you to Abby Lasky for the graphic design).

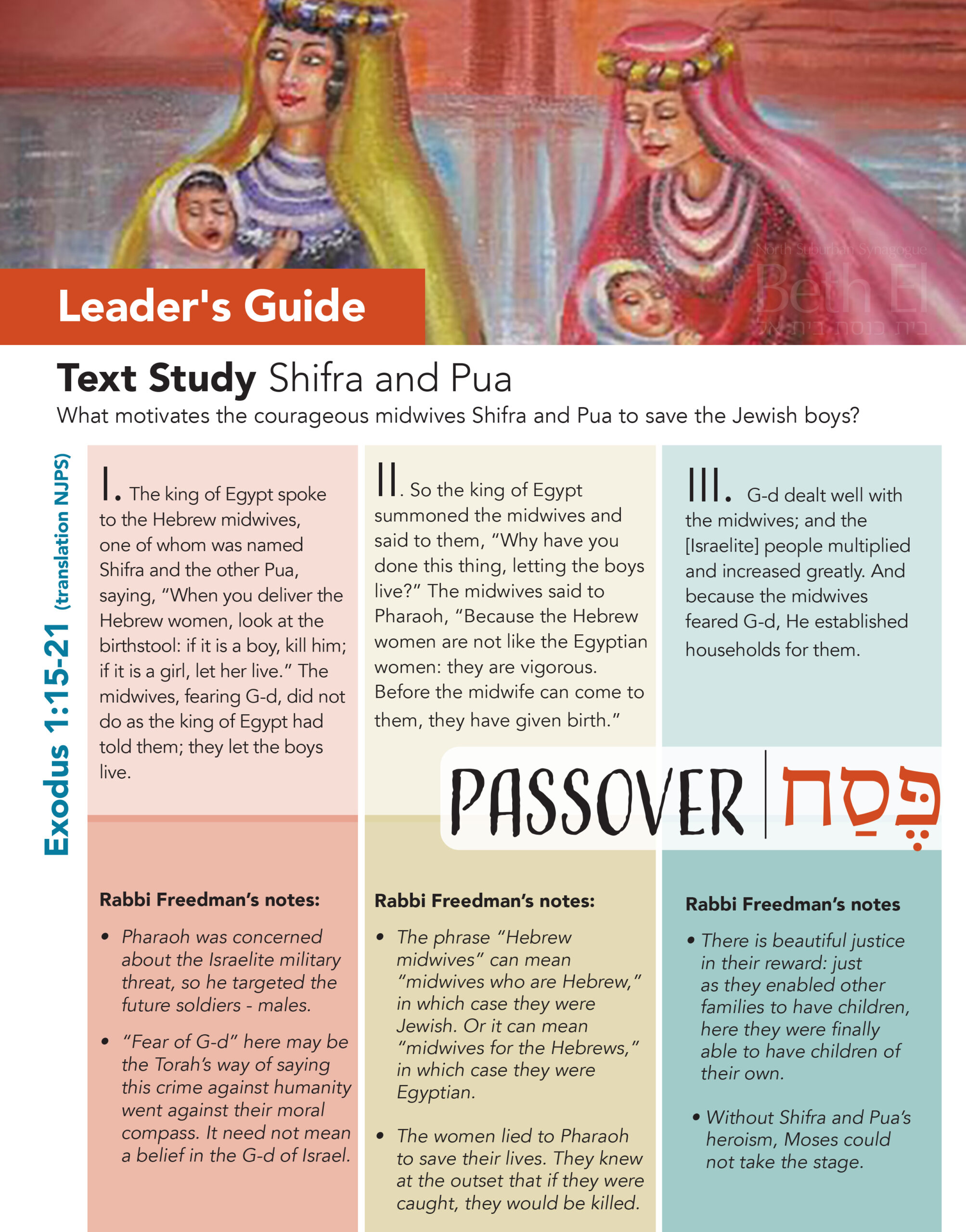

The Seder Supplement has two front-and-back pages. A few verses from the Torah tell the story of Shifra and Pua, two Egyptian heroines who defied Pharaoh’s orders and saved the Jewish baby boys from death in the Nile. Many of us didn’t learn about them when we heard the Passover story taught in Religious School. That’s a shame, for they were courageous role models. Who today models these values of courage and solidarity with all of humanity?

The second page includes different quotes about courage, inspired by Shifra and Pua. Selected from a range of personalities and historical figures, these quotes spur us to think about courage in a more sophisticated way. The Passover story highlights courageous acts by women and men, and our understanding of this inner strength should mature as we do. Our conversations should reflect this growth.

This first handout is for all the guests; print out a bunch for the table (or share the PDF with virtual guests) to start a conversation. Also print out one copy of the second handout for the Seder leader. This contains my insights on the Torah study, in order to dive a little deeper. It also includes a series of Seder trivia questions to keep things interesting throughout the night.

The Haggadah text itself is a conversation starter, but sometimes it needs to be unlocked. That’s what the Seder Supplement is intended to be. The word “Haggadah” itself means “Telling the story.” So does the Hebrew word “Maggid,” the longest section of the Seder. The Torah tells us “You shall tell your child on that day [of a future Passover holiday], ‘It is because of what G-d did for me when I left Egypt’” (Ex. 13:8). The challenge – and ultimate satisfaction – is to create an experience and conversation that makes it feel as if we ourselves taste both slavery and freedom. So we’ve got to talk about it. The conversation itself is the experience of renewed liberation. After all, only free people can speak freely.

If you’re hosting, feel free to make copies for your guests (in-person and virtual) and adapt to your needs. The hardest part is starting a meaningful conversation. Once it begins, however, it’s as sweet as Haroset.

No Seder leader can control what the guests will say and who will participate. But every Seder leader can prepare for success by organizing in advance questions, stories, songs, games, and topics for discussion.

This Passover, let’s liberate the conversation too.

Inspiring Stories of Heroic Compassion

by Rabbi Michael Schwab

“Each person shall give . . . .” (Exodus 30:12)

Two weeks ago Texas was hit with a major winter storm that brought with it uncharacteristic freezing temperatures. As a result, much of Texas was thrust into an emergency situation: thousands without power or water, plus many families who were initially stranded on roads or isolated in homes. The damage was so widespread that local authorities and services were simply overwhelmed and were not capable of helping all who needed assistance.

However, help arrived anyway, due to the kindness and generosity of private citizens and NGOs that took to heart the obligation of giving of themselves to others. Following the opening command in our Torah portion this week that each person, each soul, needs to give something of themselves to the community, individuals stepped up to rescue stranded citizens, fix broken water pipes to restore water and help save the lives of those who were in distress.

For example, as People Magazine reported, when plumber Andrew Mitchell heard of all that was needed, he and his wife, Kisha Pinnock, packed $2,000 worth of materials and drove nearly two days from their home in New Jersey to Texas, to help in the efforts. For the trip, the two also brought along their 2-year-old son, Blake, and Mitchell’s apprentice and brother-in-law, Isaiah Pinnock. They are still there helping Texans who were told by local plumbers that they would need to wait three weeks for an appointment and it could cost thousands of dollars. Because of this family, dozens of homes now have running water again.

And there is Ryan Silvey, who left his Austin, Texas, home on Feb. 15 in his truck to get a Mountain Dew and a pack of cigarettes, as snow began to blanket his city. But, as USA Today reported, quickly the weather worsened and the routine errand turned into a grueling four days spent hooking straps and chains to hundreds of stranded vehicles, pulling their passengers to safety. As he said, “If it was me and my kids in a car, or if someone was in pain, I’d hope they’d help me.” One woman, who had her dogs in her car, had to be pulled miles to her family’s home, in reverse. Another family was pulled from a ditch around midnight after their car had lost power and the dad had a head wound that was bleeding. After his story was shared by other news outlets, he was contacted by other truck and Jeep owners, offering to help. While pulling cars himself, Sivley fielded calls and text messages from other stuck drivers and delegated the jobs out to the rest of the makeshift team. He and his colleagues helped hundreds of people in danger, simply out of the goodness of their heart.

And there was Enriqueta Maldonado, who USA Today reported cooked hundreds of meals for those who were vulnerable and had no electricity and water, or a way to get food for themselves. “When we first kind of determined that we had the resources to cook food, it was honestly like a no-brainer,” she said. Monica Maldonado, her mother, called on the pastor at Teri Road Baptist Church, who donated its entire pantry full of food. Nonprofit Do Good ATX set up an online portal to sign up for meals, provided the supplies and enlisted the help of volunteer delivery drivers. So Enriqueta and Monica got cooking. Over the next week, they fed hundreds of people helping to stave off hunger for those in need.

Life is unpredictable and disaster often comes unexpectedly. We never know whether we will be the victim or the person in a position to help. However, as Jews and as human beings, one value remains constant: that we all need to find a way to give when there is someone in need. As the real life heroes mentioned above demonstrated, all we need is an open heart, a compassionate soul and a commitment to do what is right in order to make a difference.

By Hazzan Ben Tisser

Masks. As a child, I associated this word with Halloween, of course with Purim, and occasionally with my dentist. As an adult, masks remained a symbol of parties, good times, and Purim (and yes, the occasional dental appointment), and we learn to think about masks as a metaphor as well. Most recently, masks have become part of our daily lives – our suits of armor, so to speak – protecting our very lives.

For many of us, masks are utilitarian. We want to be sure they fit properly, that they offer sufficient filtration against microparticles, and that they ultimately do their job. Others of us are equally concerned with the aesthetic of our facewear, and in response fashion designers around the world have created lines of very attractive masks. Some of us cannot stand the nuisance of having our faces covered, while others of us take great comfort in the discomfort. And while literal masks are part of our wardrobe, figurative masks are still very much present.

Metaphorically speaking, we have all learned to mask ourselves at times. To wear a “poker face”, or to hide deep emotion; to hide frustration with friends or family members in favor of showing patience and understanding…and to hide those parts of ourselves we might wish others not know about. Sometimes, we hide behind a mask (or an emotional wall) when we are hurt by someone we love.

In Deuteronomy (31:16-18), God speaks to Moshe, calling him up to the peaks of Mt. Nevo, where he will ultimately die. God tells Moshe that Israel will forsake the Covenant, and that God will therefore hide God’s face from the people, but that ultimately they will return and all will be good. The Hebrew used for “hide” is a doubly-strong form (“haster astir,“ which both look and sound like Esther — I’ll get there in a moment). God predicts that God will be so hurt by Israel’s breach of the commandment that it seems God will hide behind a dozen N95’s. Perhaps that is because the people won’t, at that point, deserve to interact directly with God; or perhaps, if we can anthropomorphize God more a moment, God will be so deeply hurt that He doesn’t want His children to see that level of pain on His face…similarly to how a parent deeply hurt by their child might hold back showing deep emotion.

Purim this year is going to be different than ever before. A year ago, we still gathered. A year ago, we didn’t yet really understand what it would mean to be masked in the same way we do today. So the question becomes, how do we do Purim — how do we celebrate the holiday of hiding behind masks — when wearing masks is nothing new or special?

The answer, for me, lies in two Hebrew words many of us know — kavannah and havdalah. Kavannah, or intentionality, is the act of being mindful and purposeful about something. It means taking a moment as we put on our Purim costume and really thinking about what we are doing. It means understanding that we are dressing up for a sacred purpose, to remember the heroism and strength of one brave woman in very unfavorable circumstances over a thousand years ago. Havdalah means separation. We separate so many things as Jews – meat and dairy, the holy and the mundane, the Jewish people and the other nations of the world… This is nothing new. But in setting our intentionality, we create a havdalah–a sacred separation–between the “normal” act of putting on a mask and the holy act of putting on a Purim costume.

Purim is about being who we are not for one night. It’s about celebration and revelry. And we are all pretty good at that, at this point. I don’t think there’s much challenge there. I think the greater challenge lies in what we do the day after Purim. We will wake up the next morning, unlike any year prior, and put a mask on again. Perhaps a surgical mask, or an N95, or perhaps a fashionable mask. The challenge lies in the kavannah with which we put that mask on. How will we use it? Will we use it to hide a part of ourselves from those around us? Will we make an effort to smile and let others see what we are feeling? I would suggest that if Purim is about hiding a part of ourselves behind our masks, the havdalah becomes much more powerful if the rest of our week is about sharing and showing as much of our real selves as possible.

I therefore invite you to take a moment this evening as you put on your costume and make your kavanah, your intentionality, and to really enjoy every aspect of the holiday! But then on Shabbat morning when you put your mask on again and the holiday is over, make a new kavanah — make it somehow different, even special. Don’t hide your face or your emotion. Be open to the world, share with those around you (from a safe distance, of course!), and let your smile shine through.

Rabbi Alex Freedman

A story: There was once a Jewish village in the woods – think of Anatevka from Fiddler – where nothing ever changed. Every morning the men gathered in the synagogue for prayers, generation after generation. Until one day something changed.

A man named Aaron had stepped out of the service right before the Amidah, the most important prayer of all. Afterward, people wondered where he had gone. Why would he do that? The rabbi quelled the gossip: “I’m sure it was just one time. No big deal.”

But the next day, it happened again!

The rabbi wanted to know where he was going instead of connecting to G-d in the synagogue. So the next morning, the rabbi followed Aaron when he slipped away during the service. Aaron walked out of the village and into the woods. Deep in the forest, he found a clearing among the trees and began to pray the most pure prayer the rabbi had seen in a long time. Afterward, Aaron was startled to see the rabbi follow him. The rabbi said, “Your prayer is so inspiring! Come back to the synagogue. Because G-d is the same everywhere.”

Aaron responded, “G-d may be the same everywhere, but I am not.”

Places change us: the woods, the Kotel, the sanctuary. G-d is as present in every place as G-d is in those, but we feel more connected in those places because we are different.

Parashat Terumah describes the portable sanctuary constructed by the Israelites in the desert. G-d does not need the sanctuary to be present among the Jews. But having a dedicated space for G-d enables people to focus on the divine in a way that our living rooms do not. We need the sanctuary, not G-d.

Ironically, the pandemic has turned all this upside down (like Purim next week!). Because now more of us are tuning into services from our homes than are entering our sanctuary. This is not ideal, but we must do what we can to stay safe.

I cannot wait until we are all back in our sanctuary, whenever that day arrives. It will revitalize our social bonds with each other. Like Aaron finding spiritual solace in the woods, I hope it will strengthen our connection to G-d as well.

By Rabbi Michael Schwab

“How can we ensure that Jewish ideals—such as protecting the downtrodden and most vulnerable people in our society—emerge from the abstract and find expression in our daily lives?” In a wonderful dvar Torah on Parshat Mishpatim, Rabbi Shlomo Riskin poses this critical question. Our weekly portion, Mishpatim, gives us a powerful answer: through sincere commitment to following Jewish law. Law, which guides actual daily behavior, is the key vehicle for the tangible expression of the ideals and ethics we hold dear as Jews. For example, the Torah states in our Parsha, “When you lend money to My people, to the poor person with you, you shall not behave toward him as a lender; you shall not impose interest upon him.” (Ex. 22:24). This Torah verse takes the oft repeated values of having compassion for the downtrodden and for treating all people as fellow creations of Gd made in the Divine image, and gives them meaningful pragmatic expression. Here the poor are referred to as “My people” — under the personal protection of Gd. This is a clear statement that those who are poor are not to be treated as lesser, but as equally important and deserving of proper treatment. Therefore, giving money to the poor is not a hand-out, a favor, or even a loan, but a required righteous act that fulfills the Divine principles of justice and compassion.

Riskin points out that Rabbi Hayyim ibn Attar, in his famous work, Or Hahayim, expands on this idea in a radical way. He writes that it is likely that everyone would agree that ideally all people would have an equal share in the resources of the world and that such a share would be more than sufficient for each person’s needs. Alas, that is not how human history has played out. But, the principle still directs our attitude towards our money, and therefore our treatment of it. Based on this verse and others, he claims that those who have more resources are merely holding those resources on behalf of Gd for those who have less. So, when we “lend” a poor person money it is not a true loan, as that money is actually part of their fair share. The affluent, therefore act as Gd’s sacred agents in the just allocation of Gd’s resources. As Riskin states, “This is the message of the exodus from Egypt, the seminal historic event that formed and hopefully still informs us as a people: no individual ought ever be owned by, or even be indebted to, another individual. We are all “‘owned by’ and must be indebted only to Gd.”

This is a foundational truth of our traditional legal system, which, therefore, gives us specific laws and actions that provide for the needs of the downtrodden and enslaved, the poor and the infirm, the orphan and the widow, the stranger and the convert. From this perspective, not only must we value Jewish law in order to preserve our ethical principles, but it is crucial that we ensure that Jewish law remains true to its ethical foundations in the way it is practiced each and every day.

By Hazzan Barbara Barnett

This week in Torah, the journey of our ancestors continues, leading them to the foot of Mount Sinai, where Moses disappears for forty days to talk with God and return with the Ten Commandments. It’s a pivotal moment coming early in the journey from Egypt to the Promised Land and the “aseret hadibrot” (the ten words, as one might translate the Hebrew) frame the entirety of the 613 commandments (mitzvot) contained in the Torah. Mitzvot that to this day provide structure and scaffolding to live a good Jewish life.

The Torah was given to the Israelites, a precious gift, and even the angels, says our tradition, were astounded that such a thing should be put into the keeping of mere mortals. But the Torah is ours, not just an artifact of an ancient time, but living, breathing document to be turned and studied and interpreted and re-interpreted to guide us.

Over the generations, the words of the Torah were inscribed onto parchment scrolls, from which each week we can study its words and explore its depths and meaning for us in our time.

North Suburban Synagogue Beth El is blessed to have numerous Torah scrolls. Most weekdays when we read Torah publicly and on Shabbat, we only need a single Torah; there are some Shabbatot where we need up to three! (February 13 is one of those rare three-Torah days).

But Torah scrolls are handwritten in quill and ink on heavy parchment, and over time and with use (and sometimes with lack of use), the letters fade, flake off or something else goes wrong with the physical scroll and the writing. And the Torah scroll in order to be considered “Kosher” and appropriate to read publicly must be in perfect condition.

When we identify a problem, it needs to be repaired. Perhaps a letter needs to be re-inked meticulously and as an exact match to the hand that is in the original scroll. Perhaps an entire section needs re-inking or replacing.

So every once in a while, it’s a good idea to have all the Torahs checked to make sure they are in perfect condition for use. And to identify issues—and fix them.

Next week we will be hosting a visit from Sofer on Site, a company specializing in Torah repair and restoration. Rabbi Moshe Druin, one of their master sofrim (scribes) will visit Tuesday and Wednesday first to evaluate all our Torahs and initiate repairs. Wednesday, February 10, everyone will have an opportunity view him at work via the “Torah Cam,” which will be placed in the Zell to allow us a bird’s eye view of Rabbi Druin as he repairs our Torahs. He is happy to answer questions and explain what he is doing if you stop by any time between 10 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. on Wednesday. Questions before Rabbi Druin’s visit? Feel free to email me at bbarnett@nssbethel.org.

by Rabbi Alex Freedman

Trees provide us with so much: oxygen, shade, fruit, and metaphors.

One of my all-time favorite teachings centers around trees:

The Talmud (Taanit 23a) shares a short story:

One day [Honi the circle maker] was walking along the road when he saw a certain man planting a carob tree. Honi said to him: “How many years does it take for this tree to bear fruit?”

The man said to him: “70 years.”

Honi said to him: “Is it clear to you that you will live 70 years [and benefit from this tree? Why are you planting this if you will not be around to see it in full bloom?]”

He said to [Honi]: “I found a world full of carob trees. Just as my ancestors planted for me, I too am planting for my descendants.”

Honi sat and ate bread. Sleep overcame him and he slept. A cliff formed around him, and he disappeared from sight and slept for 70 years. When he awoke, he saw a certain man gathering carobs from that tree. Honi said to him: “Are you the one who planted this tree?”

The man said to him: “I am his grandson.”

I am captivated by the image of planting: One seed – when planted – can yield an entire tree, which can grow and produce more seeds to become an entire grove. Just like one person can become the top of a family tree with countless branches.

I love that the anonymous man appreciated that the resources around him were provided by others. He woke up on third base and did not think he hit a triple.

I am moved by the man’s reflex of responsibility. Though nobody tells him to, he intuits that he has an obligation to others he cannot even see.

I am touched that the man’s grandson finds himself in the very same place where his grandfather once planted. The very one to benefit from the grandfather’s tree is not a stranger but family.

May we – grandparents, parents, children, and grandchildren all – enjoy the fruit of previous generations, and may we plant more for those who follow us.

By Hazzan Tisser

In 2016 I had the privilege to participate in the Cantors Assembly’s historic mission to Spain. Dozens of cantors and hundreds of our congregants joined us as we traveled the country for two weeks, learning about the history of Spain and of our people in it, performing in concerts, and meeting the local Jewish communities. It is an experience I will never forget.

Surprisingly, one of the most memorable parts of our trip was a bus ride to Toledo. We drove for several hours through the countryside, eventually ascending the hills to the ancient city. As we drove, passing the occasional village, what stood out were the groves of olive trees spread around us. They stretched for miles, seemingly unending, against the brown landscape. As the tour guide spoke about the trees, he mentioned that these trees no longer bear fruit. Naturally, someone asked why. The tour guide shared with us that these trees were many centuries old, some more than 1,000 years old, and that at a certain point olive trees stop bearing fruit. At the same time, the Spanish people would never think of taking down the ancient trees in order to make room for new, fruitful ones.

Earlier this week our family observed the second yahrzeit of my wife’s son, Isaac. We gathered with friends and family on Zoom to remember him, celebrate his life, and pray. As I thought about it, the olive trees can teach us much about our time in this world and what happens when our time comes, hopefully after many good years. We are given the gift of life. We are each given a unique set of skills, talents, and aspirations. We have everything we need to succeed, just as the tree does. If trees are cared for, receive proper rain and sunshine, they bear much fruit. At some point, our time in the world is up and we will be held to account for all we did in life.

This is a challenging subject to think about or to discuss, but I think our task is clear: to live lives that leave a lasting impact on the world; to live lives which will stand firm in the memories of those who come after us. We can do this by living lives inspired by Torah, filled with the beauty of our tradition. We can do this by caring for the other as much as we care about ourselves. We can do this by passing on family traditions to our family and friends, by teaching them to our children.

The olive trees along that highway in Spain stand firm because the people who live there understand the value of the fruit they once gave, and see it as their duty to maintain the memory of that in a very real way. Next week is Tu Bish’vat – one of the four Jewish new years, when we celebrate trees and the natural world around us. With each new year comes the opportunity to recommit to our resolutions, our values, and to ourselves. Let us use this holiday, then, as an opportunity to reflect on our lives so that me may, as the Psalms teach, flourish like the palm tree, still bearing fruit in old age.

Finally, I hope you will join me for our Tu Bish’vat seder, next Wednesday, January 28, at 6:45 pm, on the Daily Minyan/Shabbat Schmooze Zoom link. We will sing, share readings, eat, and of course thank God for all that is good and beautiful in the world.

“See” you in shul,

by Hazzan Barbara Barnett

“R’fa’einu Adonai v’nei’rafei

Hoshieinu v’ni’va’sheiah”

We recite these words in every weekday Amidah—a prayer for healing: “Heal us, Adonai, and we shall be healed. Save us and we shall be saved.” We then we ask God to grant “refuah shleima,” perfect healing, for all our afflictions.

Over the course of the pandemic, I have paused a moment at this blessing each morning and evening, thinking about those I know personally who are afflicted with COVID (that list seems to be growing by the day). Since election day (and even more so this past week in light of the events at the Capitol last Wednesday), I’ve been thinking about this Amidah blessing in a more societal sense.

We say (both in this blessing and in the Misheberach prayer we recite at the Torah) “Refuat hanefesh u’refuat haguf” (heal the spirit and the body—the seen and the unseen wounds and illnesses).

How do you go about healing a wounded country? Heal we must, but it’s not as easy as saying a prayer and hoping for the best. The healing process will be messy and rocky, difficult and very challenging. But, the process begins within each of us, a commitment to V’ahavta l’rei’acha kamocha, “Love your neighbor as yourself,” as the Torah says. Or in the words of Rabbi Hillel “What is hateful to you, don’t do to anyone else.” These are the essence of Torah, the essence of the moral wisdom embodied in the commandments. It’s easier said than done and ultimately cannot be accomplished without being intertwined with justice.

It starts with us as individuals (hey, God can’t do it alone) and, like ripples in a pond, resonates to family, to community and beyond. Rabbi Menachem Creditor wrote a simple, but evocative song—a prayer, really, for his infant child in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. (You can see him sing it here) It is equally meaningful and profound in the aftermath of last week, as we pray for a peaceful transfer of power and for the new administration:

Olam Chesed Yibane

I will build this world with love

And you must build this world with love

And if we build this world with love

Then God will build this world with love.